ON THE DIVINITY

OF EL GRECO

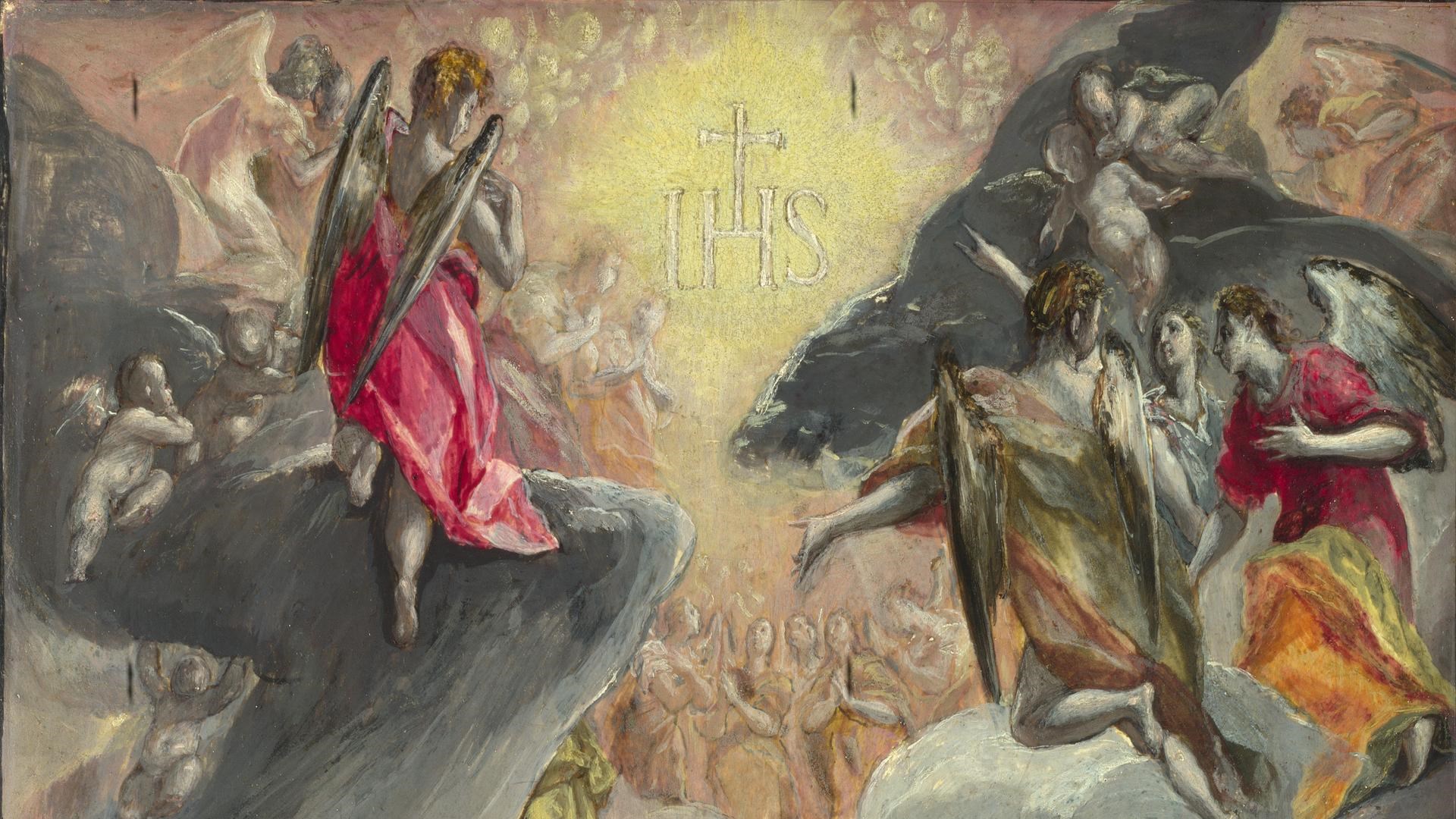

El Greco - The Adoration of the Name of Jesus (1577-1579, detail)

El Greco (1541 – 1614) was a mannerist painter. Known for his uniquely strange style, he was a large source of inspiration to the expressionists and cubists, centuries after he passed away. The figures painted by El Greco seem unnaturally elongated; their surroundings are twisted and constantly moving. Looking at El Greco’s work gives the viewer a glimpse into a strange world, inhabited by saints, martyrs, and, often, Christ himself.

El Greco’s role in the story of ‘De protodood in zwarte haren’ is implicit, yet vital. Pedro and his companions Béatrice and Charles Charron visit the Cathedral of Toledo, which is home to ‘The Disrobing of Christ’ (1577 – 1579): one of El Greco’s most enchanting paintings. The work shows Jesus Christ being prepared for his crucifixion. The stretched-out figure of Christ is seen wearing a red robe, which is about to be taken off by the man standing to the right of him. Christ looks away from the chaos he is the centre of, as though he has already left his earthly body. He is looking towards the sky, towards the divine, gradually moving away from the contingency of life.

‘The Disrobing of Christ’ (1577-1579, detail) was made by El Greco for the Cathedral of Toledo, where it can be found in the sacristy.

The aforementioned sense of moving toward the divine is echoed in the novel, where El Greco’s painting becomes Pedro’s first encounter with the spiritual in art. The witnessing of ‘The Disrobing of Christ’ is what art theorist and expressionist painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866 – 1944) would have called ‘spiritual bread’: it feeds Pedro’s soul and guides him towards the discovery of Modernism, the art movement he will ultimately use to attempt to deconstruct physical reality. The holy aspect of ‘The Disrobing of Christ’ is emphasized by the fact that Pedro’s primary encounter with it is during a vision he has whilst entering the cathedral.

After the vision, Pedro walks towards the sacristy, in order to experience the actual painting. Béatrice Charron appears behind him and startles him. She seductively approaches Pedro and tells him to paint her naked body once they arrive in Paris. Pedro, who is both confused and frightened, slowly walks away from her, towards the painting behind him.

The fact that Pedro is caught between the sexual energy of a young woman and the holy painting by El Greco has symbolic significance. The sexual transgressions Béatrice instigates inside Pedro’s mind are a reference to George Bataille’s (1897 – 1962) ‘L’Érotisme’ (1957), in which sexuality, death and the divine are interconnected by acts of transgression. Sexual fantasies, as expressed by Béatrice Charron, push Pedro away from the disappointing banalities of real life, bringing him closer towards an idealized word; an abstraction. Thus, through Béatrices words and movements, Pedro moves towards the painting, metaphorically incorporating himself into it, becoming Christ.

‘Transverberation of Saint Theresa’ (1647–1652, detail), by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 – 1680). This image, which is used by Bataille in L’Erotisme (1957), is a prime example of spiritual ecstasy fused with eroticism and physical suffering.

The composition of the song ‘El Greco in Toledo’ on ‘Zwart vierkant’ is both estranging and destructive. It is a symbolic revelation, a spiritual trumpet, blown in order to invoke a feeling of abstraction. The lyrics make reference to Amdusias/Amducias: one of the 72 spirits of Solomon, mentioned in the ‘Ars Goetia’: a 17th-century grimoire on demonology. Amdusias is a great duke of Hell, who has the power to cause trumpets and other musical instruments to be heard and not seen. Amdusias is credited as being the demon in charge of the cacophonous music that is played in Hell.

‘Amduscias a great and a strong duke, he commeth foorth as an unicorne, when he standeth before his maister in humane shape, being commanded, he easilie bringeth to passe, that trumpets and all musicall instruments may be heard and not seene, and also that trees shall bend and incline, according to the conjurors will, he is excellent among familiars, and hath nine and twentie legions.’

Quote from the ‘Ars Goetia’, mid 17th-century

The demon Amdusias resides in Jinnestan, the capital of which is named the City of Jewels. The mentioning of blaring trumpets throughout the City of Jewels is also a reference to the city of Toledo; the Cathedral of Toledo is filled with overwhelmingly expensive Baroque ornaments and sculptures. As Pedro travels further up north, so does the cacophony of his unseen abstraction.

Revelation of the secret: modernism, hidden in passion. Throughout the south and the north now blare the trumpets of Amducias. Reverberating cacophony sounds inside the city of jewels.

Lyrics from El Greco in Toledo

Actual recordings of the ambience inside the Cathedral of Toledo were recorded for ‘Zwart vierkant’ by the band. Both the sounds of the one-armed clock and the sacristy were used on the album. The use of the latter is a minimal recording, with not much more than silence and the respectful whispering of visitors inside the cathedral, but its usage is of more of a symbolic and spiritual nature. It is used as a sonic background throughout the entire song, creating a sense of depth, instead of static silence. For a brief moment, it sonically puts the listener in front of one of El Greco’s most impressive paintings.

The Toledo scenes in ‘De protodood in zwarte haren’ were edited and partly re-written during a stay in the Hotel Santa Isabel in Toledo: a 15th-century building, only two minutes away from the cathedral. The cathedral was visited daily for three days; actual routes were planned out to move the characters through the scene.